What np Charts Can Tell You

Michael J. Cleary, Ph.D.

mcleary@qualitydigest.com

Hy Sedrate, director of quality

for St. Recover in the Longrun Hospital, has been worried

about his organization's future and, more specifically,

about his own. Through a series of complex arrangements,

St. Recover has been acquired by Santa Cura Hospitals, a

large regional organization made up of some two dozen hospitals

and clinics.

Sedrate has learned to manage quality systems at St. Recover--but

only through the prowess of his SPC team, which works nonstop

analyzing hospital data.

Sedrate knows that he won't be promoted to the larger

organization without a dramatic demonstration of quality

improvement in his organization. The alternative is grim

because there are apparently plenty of other quality directors

in the same position within the Santa Cura system.

After walking around the hospital and considering the

possibilities, Sedrate determines that a highly visible

project he's capable of supervising concerns the number

of medications that are either incomplete or inaccurate

when they're delivered from the pharmacy.

"Prescription drugs are always in the news,"

he muses, "so everyone will notice our improvement."

With that confidence, he arranges for the pharmacists

to gather data relating to missed medications. Sedrate knows

he'll have plenty to work with because the pharmacy has

been collecting data for the Joint Commission on Health

Care Accreditation. He decides that the data should be considered

as attributes data because he'll be measuring nonconforming

items, defined as those medications that fail to be delivered

on time. Further, he believes that an np chart is the appropriate

way to analyze the data because, in effect, he'll be examining

the number of deliveries with mistakes.

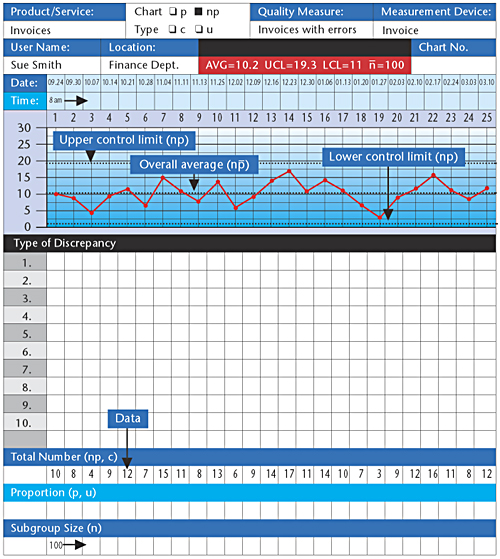

He develops the chart below, based on the data provided

by the pharmacists.

However, when Sedrate analyzes the chart, he's disappointed

that the system seems to be in control. "I was hoping

to see lots of out-of-control points so we could eliminate

special causes," he mutters to himself, deciding that

the np chart gives him nothing dramatic with which to enhance

his portfolio in the hospital. He's so worried that he finds

himself losing sleep at night. Is his anxiety merited?

Sedrate's high blood pressure is pointless because the

pharmacy process gives him plenty of opportunities to improve

quality. The point is not just to identify out-of-control

conditions but to improve the process. The np chart reflects

that the process is now generating an average of 10.2 nonconformities

per week.

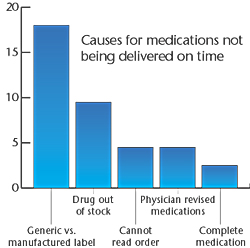

By brainstorming and using cause-and-effect analysis,

Pareto diagrams and other problem-solving and data-analysis

tools, Sedrate's improvement team can identify ways to further

reduce the number of missed prescriptions.

Quality improvement isn't simply gathering data but analyzing

data and organizing it in order to determineways to improve

a process. The plan-do-study-act cycle focuses on continuously

examining processes in order to bring them to even greater

levels of predictability.

Michael J. Cleary, Ph.D., is a professor emeritus at Wright

State University and founder of PQ Systems Inc. He has published

articles on quality management and statistical process control

in a variety of academic and professional journals. His

Web site is www.pqsystems.com.

Letters to the editor regarding this column can be e-mailed

to letters@qualitydigest.com.

|