by Laura Smith

Trying to pin down the exact problem with the U.S. auto industry is like trying to map the roots of a tree: Where do you start?

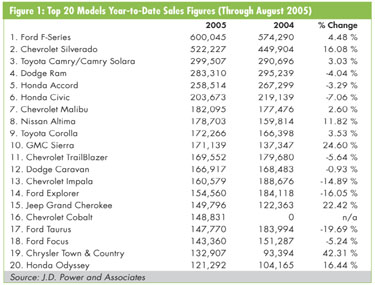

The industry's problems are numerous: declining market share (even with extravagant cost-cutting), massive recalls, tumbling stock prices, layoffs and steep legacy costs. Autodata Corp. reports that the Big Three (General Motors Corp., Ford Motor Co. and DaimlerChrysler Corp.) control 58.7 percent of the global automotive market; their Asian counterparts, on the other hand, have almost half of that number--31 percent. But that 58.7 percent is an all-time low, down from a high of more than 70 percent in 1998. Taken as a whole, the Big Three's market share declined this year, although DaimlerChrysler's actually rose by about a half-percent, according to J.D. Power and Associates. The rating agency reports that the increase was mainly due to strong sales of DaimlerChrysler's Jeep and Grand Cherokee nameplates. (See figure 1.)

As evidenced at August's AutoTech trade show, sponsored by the Automotive Industry Action Group, automakers are clearly doing some soul-searching. Dozens of speeches, workshops and panels trumpeted one common theme: To survive and thrive in the highly competitive global automotive market, the Big Three has to cooperate more than ever before.

Big Three executives have long blamed retired workers' skyrocketing health care and pension costs for much of their companies' financial woes. Looking at the figures, it's easy to see why. Ford, GM and DaimlerChrysler agreed to provide health insurance for the life of their United Auto Workers-affiliated employees when their contracts were initially written, and the cost of that insurance for retired workers alone adds an extra $1,200-$1,800 to the cost of each Ford, GM and DaimlerChrysler car, according to the AIAG.

Japanese automakers offer their employees health plans that are comparable to their U.S. counterparts, but the Japanese government provides health-care benefits to retirees, an important benefit that saves Toyota, Honda and other Japanese automakers billions of dollars each year. GM, Ford and Daimler-Chrysler spent $3.6 billion, $2 billion and $1.3 billion, respectively, on retiree health care last year, but the cost of retiree health care to Toyota is so small that it isn't even listed as a line item in its financial statements, according to AutoWeek.

Add to those figures the fact that profit margins on almost all nameplates, particularly those of the Big Three, are shrinking, and the disparity between U.S. and Asian automakers becomes clear. According to the 2005 Harbour Report, a well-respected study that examines the North American automobile manufacturing industry, the average profit per North American-manufactured vehicle breaks down as follows:

• Nissan: $1,603

• Toyota: $1,488

• Honda: $1,250

• Ford: $620

• DaimlerChrysler: $186

• General Motors: ($2,311)

"Labor concerns are a huge issue for the Big Three right now, and they're a lot more complicated to resolve than simply boosting efficiencies and moving more cars off of the lots," says Tom Libby, J.D. Power and Associates senior director of industry analysis. "Before Ford, GM and DaimlerChrysler even get their cars assembled, they're already playing catch-up to Toyota and Honda. It won't get better until they solve the health-cost issue."

But pricey health plans aren't the root of all the Big Three's problems. The UAW has correctly pointed out that companies can't shrink their way to profitability, and the organization has refused to give up full retiree health-care benefits. However, a recent deal between GM and the UAW allows GM to trim retired workers' health-care coverage, cutting GM's retiree health-care liability by about $15 billion.

Ron Gettelfinger, UAW president, has called for concessions in executive pay. It should be noted that GM Chairman and CEO Rick Wagoner earned $4.8 million in 2004, down from $8.5 million in 2003, and outgoing DaimlerChrysler Chairman and CEO Juergen Schrempp earns an estimated 10.8 million euros a year. William Clay Ford Jr. announced earlier this year that he won't take a salary until his company is profitable again.

After Moody's Corp. cut GM and Ford's debt to junk-bond status in August, Ford ordered a series of cost-cutting and capital-raising moves, including the sale of its Hertz rental car agency, the reduction of 2,700 North American jobs and the restructuring of its marketing operations.

"The downgrades reflect further erosion in the operating results and cash-flow generation of Ford in consideration of weakened market share and continued challenges in addressing its uncompetitive cost structure in North America," William Clay Ford Jr. said in a statement announcing the changes. He later hinted that the company is rethinking its entire marketing strategy.

"It's not just about cutting, cutting, cutting," Ford told The Wall Street Journal. "There is that element, but it's also about where you are headed, what you stand for. That's something we're going to have a lot more to say about as we go forward."

GM and DaimlerChrysler have made similar cutbacks. This summer, GM announced plans to cut 25,000 jobs by 2008 as part of a four-step plan to invigorate its North American operations. Other steps include increased investment in developing new cars and trucks, clarifying the role of each of GM's eight brands, intensifying cost-cutting and quality-improvement efforts, and health-care cost reduction.

There's no doubt that these are historic times for domestic auto manufacturers. Jim Queen, GM's vice president of engineering, acknowledged in an interview with The Detroit Free Press that there is internal frustration, too.

"I'd be dishonest if I didn't say that there are several of us that are somewhat frustrated at the inability to move the product," Queen said. "But perception is reality. If you look at quality and the losses we sustained over decades there, it's going to take us some time to get back to where we want to get. Rationally, we know that. But there's also an ego part, a fundamental human spirit, that gets frustrated when some of the products don't resonate the way we feel they should in the marketplace."

Ironically, U.S. quality experts first taught Japanese automakers much of what they know about quality. When the Union of Japanese Scientists and Engineers (JUSE) invited W. Edwards Deming and Joseph M. Juran to deliver lectures in 1950 and 1954, respectively, Japanese managers' approach to quality control emphasized statistical methods and control charts, says Peter J. Kolesar, Columbia University professor and Juran Institute board member.

Juran and Deming's Japanese lectures have taken on a kind of mythic status in the quality profession, though Juran himself was always dismissive of the claim that they were responsible for the post-World War II manufacturing boom that built the Japanese reputation for quality. However, Kolesar's examination of the lectures shows that Juran was probably overly modest in his claims.

The thrust of Juran's lecture series was that to be effective, quality must be the top priority of an organization's senior managers. He emphasized the importance of design quality and outlined these five primary responsibilities of top executives:

• High policy or doctrine on quality

• Choice of quality design

• Measurement of results

• Development of an organizationwide quality philosophy

• Results reviewed against goals and action taken on significant variations

According to Kolesar, who reviewed Juran's copious notes from his lectures, Juran told the audience: "It is axiomatic that if the enterprise is determined to remain in business for a long period of time, the quality of the product or service which it is selling must be adequate to meet the needs of the customer. Failing this the consumer will justifiably turn to other, competing products or services which do meet needs."

Deming's approach was similar to Juran's. Deming preached the importance of statistical control and quality measurement, updating the old "design it, make it, sell it," manufacturing model with the added step of market research, allowing continuous improvement through constant redesign in response to customer likes and dislikes.

It's clear that these lectures had profound effects on Japanese manufacturers. The themes of Juran's and Deming's presentations are now hallmarks of world-renowned Japanese quality, especially in automobile manufacturing.

The burst of manufacturing energy, marketing savvy and consumer confidence that resulted from Japanese-made cars' improved quality gave the Big Three a run for its money starting in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The big, heavy, U.S.-made cars that had been so popular through the '50s and '60s lost their magic during the energy crisis of the 1970s, when consumers wanted the lighter, more fuel-efficient cars made by Toyota and Honda. In many ways, the Big Three, so complacent with their large market share until then, has never recovered.

"The Big Three started trying to compete by improving quality and making that a marketing message in the '80s and '90s--Ford's 'Quality Is Job One' campaign, for example--but they started so much later than the Japanese that it's been very hard for them to make up that difference," says Joseph A. De Feo, Juran Institute president and CEO.

Ironically, drivers seem to think that the quality of U.S.-made cars is poorer than it actually is. Although the perceived quality of Big Three-made cars lags well behind Toyota, Honda and other Asian brands, Ford, GM and DaimlerChrysler have made giant leaps in catching up to their Asian rivals.

Consumer Reports and J.D.

Power's most recent reports bear this out: There is now virtually no significant difference in the Initial Quality Studies of problems per 100 vehicles (PP100) between Big Three and Asian-made cars. The entire industry, in fact, has made progress in reducing defects and improving quality. As can be seen in figure 2, between 1998 and 2005, the industrywide average number of PP100 across all makes and models dropped steadily, from 176 to 118.

In J.D. Power's 2005 Initial Quality Study, released in June, Toyota Motor Corp. and General Motors Corp.--the two largest automobile manufacturers in the world--captured 15 of the top 18 model-segment awards. This was particularly good news for GM, which poured millions of dollars into quality improvement at its supplier plants in recent years. But the good news was tempered by the American Customer Satisfaction Index report, released in September, which found that, although the Big Three have improved their customer-satisfaction ratings, simultaneous significant satisfaction-rate increases by Asian automakers

left the Big Three even further behind. GM's Pontiac division, for example, increased its ACSI score from 79 in 2004 to 80 this year, but Toyota's score increased from 84 to 87. In J.D. Power's 2005 Initial Quality Study, released in June, Toyota Motor Corp. and General Motors Corp.--the two largest automobile manufacturers in the world--captured 15 of the top 18 model-segment awards. This was particularly good news for GM, which poured millions of dollars into quality improvement at its supplier plants in recent years. But the good news was tempered by the American Customer Satisfaction Index report, released in September, which found that, although the Big Three have improved their customer-satisfaction ratings, simultaneous significant satisfaction-rate increases by Asian automakers

left the Big Three even further behind. GM's Pontiac division, for example, increased its ACSI score from 79 in 2004 to 80 this year, but Toyota's score increased from 84 to 87.

Although it's true that Big Three-made cars are of better quality than ever, consumer perception, especially in North America, hasn't kept up with reality. Lingering doubts about the quality of Ford, GM and DaimlerChrysler-made cars, due in part to a few large recalls, has made customers wary of buying these nameplates. In fact, Ford just announced the recall of 3.8 million trucks and SUVs, the fifth-largest vehicle recall in U.S. history.

"Once there's a bad experience, or someone hears of a bad experience with a Big Three car, that perception lingers for years," says J.D. Powers' Libby. "And in this industry, perception is reality, unfortunately. That's something these companies are working on, and will be working on for a very long time."

The influence of lean manufacturing and suppliers' adherence to standards such as ISO/TS 16949 has made industrywide assembly more competitive, too. Between 2003 and 2004, DaimlerChrysler and GM made significant improvements in the number of hours it takes to assemble vehicles: In 2003, it took DaimlerChrysler workers an average of 33.86 hours to assemble a single vehicle; in 2004, it took 25.17 hours. GM's figure dropped from 31.98 hours in 2003 to 23.09 in 2004. Ford's figure dropped only slightly, from 24.87 hours to 24.48 hours.

But even with the Big Three's substantial cycle-time improvements, Toyota, Honda and Nissan still outperform them significantly in assembly time. As of 2004, it took Toyota an average of 20.62 hours to assemble a car (down from 21.63 hours); Honda improved its assembly time from 21.41 hours to 19.46 hours; and Nissan reported the shortest assembly time of all: It takes Nissan workers just 18.29 hours to assemble a car, down from 19.20 hours in 2003.

The savings from more efficient production makes Toyota, in particular, a difficult competitor for domestic manufacturers. "Toyota's labor productivity lead equates to a $350 to $500 per vehicle cost advantage relative to domestic manufacturers," says Ron Harbour, president of Harbour Consulting. "The ironic twist to Toyota's performance as one of the most productive auto assemblers is that it is the most vertically integrated auto manufacturer, outsourcing the least of any."

The effects of North American autoworker unionization can't be understated. Membership in the UAW has decreased sharply since its heyday in the late 1970s, when it claimed 1.5 million members. As of 2003, there were just 624,585 UAW members. Unions represented 48 percent of U.S. autoworkers in 1999, down from 61 percent at the beginning of the decade. Although auto industry employment grew by more than 100,000 in the 1990s, the number of union members dropped by 51,000. The UAW has acknowledged the decline in union density, which can be seen in figure 3.

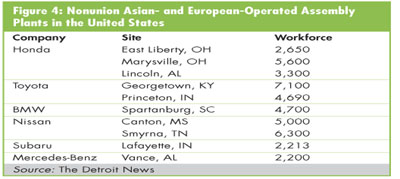

Taking note of the shrinkage, the UAW has heavily lobbied Toyota workers in the southern United States, but its efforts to organize there have been unsuccessful. In May, union organizers finally closed their office in Georgetown, Kentucky, after trying for two decades to organize Toyota's 7,100 workers in that city's plant, where the popular Camry is built. The union has also failed to organize workers at foreign-owned plants in Smyrna, Tennessee; Marysville, Ohio; and Vance, Alabama, according to news reports. (See figure 4.) Taking note of the shrinkage, the UAW has heavily lobbied Toyota workers in the southern United States, but its efforts to organize there have been unsuccessful. In May, union organizers finally closed their office in Georgetown, Kentucky, after trying for two decades to organize Toyota's 7,100 workers in that city's plant, where the popular Camry is built. The union has also failed to organize workers at foreign-owned plants in Smyrna, Tennessee; Marysville, Ohio; and Vance, Alabama, according to news reports. (See figure 4.)

Toyota workers in the Georgetown plant reportedly earn about $24 an hour, which is slightly less than UAW-represented employees make, but Truth Finders, an anti-union group at the plant, points out that workers are provided 24-hour day care, an on-site discount pharmacy and a credit union, along with other perks like parties for perfect attendance that feature big-name talent like Jay Leno.

Additionally, the old adage that unionized workers make more money than their nonunion peers is less true now than it used to be. According to the UAW, in 1990 unionized autoworkers earned 85 percent more per week than nonunion workers. By 1999, the premium had fallen to 59 percent. In the Midwest and South regions, where auto industry employment is concentrated, inflation-adjusted earnings rose 8 percent and 14 percent, respectively, for union workers; for nonunion work-ers, they jumped 23 percent and 27 percent, respectively.

There's no denying that U.S. innovations created the modern automobile. Innovation has always been strong in the United States, especially in the manufacturing sector. But Asian businesspeople have been just as successful with process perfection and careful quality improvement as their U.S. counterparts have been with innovation. This puts U.S. manufacturers in the awkward position of watching Asian manufacturers reap the benefits of U.S. innovations.

"Americans are close to perfect when it comes to innovation," says Subir Chowdhury, ASI Consulting president and CEO. "But they're not as good with perfecting designs or processes. So when the customer brings home that great car that he or she saw on the lot and it has some problems that were overlooked on the assembly line, that's going to turn that consumer off to that brand for a long time."

Foreign-based automakers, particularly Toyota and, more recently, Hyundai, have based their success on waiting for U.S. innovations and then perfecting the processes that make them. Chowdhury's new book, The Ice Cream Maker (Currency

Doubleday, 2005), addresses this phenomenon.

"I'd go so far as to say it's almost a DNA issue for Americans," Chowdhury says. "The whole culture is driven by the next quarter, and the next quarter. The mindset is still this firefighting mindset with quality. They're still inspecting for errors after they've already been created, and the Japanese and the Koreans are way ahead of them. They're designing their cars to prevent problems, and that's the future."

He adds that Asian automakers have been very successful and innovative in creating long-term partnerships with their suppliers, which prevents the need for mass outsourcing.

Chowdhury forecasts a dire future for the Big Three, if they fail to embrace fundamental changes in their corporate mentality. "Unless they make strong partnerships with their suppliers and unless they improve reliability by improving engineering, there's no way they can compete long-term

with ," Chowdhury says. "In fact, I think things will get 10 times worse for them unless they make

drastic changes."

Market forces have compelled all major automakers to make improvements in their manufacturing processes in recent years. Deep cultural differences, along with union contracts, labor pressures and differing philosophies, have made competition particularly fierce between Asian and U.S. automakers. But there are signs that drastic changes are coming for automakers from both sides of the world.

The AIAG estimates that global automakers will introduce 400 new models by 2008, a sign that their operations are becoming more nimble as they shift production to accommodate differing needs on the same assembly lines. Experts forecast that low-volume, high-variability production will become the operational norm, a characteristic at which Japanese automakers, and Toyota in particular, are particularly adept. Ford, GM and

DaimlerChrysler will have to prove they are just as good, if not better, to win in this highly competitive market.

Laura Smith is Quality Digest's assistant editor

|