ISO 9001:2000 Update

The year

2000 revision of ISO 9001 has made its way to a Final Draft International Standard _________________________________

by Jeanne Ketola and Kathy Roberts At the July ISO Technical Committee 176 meeting in

Kyoto, Japan, the Draft International Standards (DIS) of ISO 9000, 9001 and 9004 were approved, thus moving these documents to the FDIS (Final Draft Internal Standard) phase. This means that

these three revised standards are now undergoing the final round of their revision process. The stand-ards should be released by the end of the year. A quick background on the revision process The revision process demands many hours of work by quality professionals from

around the world. Committees have been meeting for the last five years at both national and international levels, hashing out vocabulary and process models as well as realigning paragraphs of

information in an attempt to create a standard that meets the needs of the end user. More than 3,000 comments were received regarding the ISO 9001 and ISO 9004 DIS. These comments were taken into

consideration during the Kyoto meetings. While several modifications to the DIS have been made, most are title changes, clarifications or other editorial changes. It's important to note that the

intent of the standard has remained the same from the DIS to the FDIS stage. How the revisions came about

The ISO 9000 family of standards is on a five-year revision cycle. The first revision occurred in 1994 after the initial release of the standards in 1987. In order to gather feedback from

the end user, a survey was sent out by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) in 1997 to a random sample of companies to determine what changes were needed to the ISO 9000

standard series. Users were critical, stating that the standards were cumbersome, not functionally oriented and manufacturing-biased; offered no linkage of methods for a unified business

approach; and didn't provide a systematic approach. Users also wanted the standards to focus on processes, customers and continual improvement. With this in mind, the ISO

Technical Committee 176 (Subcommittee 2) developed a process model to depict generic requirements of a quality management system as linked processes. The process model concept was based on eight

quality management principles:  Customer-focused organi-zation Customer-focused organi-zation

Leadership Leadership

Involvement of people Involvement of people

Process approach Process approach

System approach to management System approach to management

Continual improvement Continual improvement

Factual approach to decision making

Factual approach to decision making

Mutually beneficial supplier relationships

Mutually beneficial supplier relationships

The result of these considerations gave way to a new format for the ISO 9001

standard that addresses the basics of a unified process approach by categorizing the organization's activities into five sections. These five sections emphasize the new

process approach as follows:  Section 4 Quality management system--the global requirements for the quality management system, including the requirements for documentation and record requirements

Section 4 Quality management system--the global requirements for the quality management system, including the requirements for documentation and record requirements

Section 5 Management responsibility--the responsibilities of top management for the quality management system, including management commitment, customer focus, planning and internal communication

Section 5 Management responsibility--the responsibilities of top management for the quality management system, including management commitment, customer focus, planning and internal communication

Section 6 Resource management--the requirements of resources for the quality management system, including the requirements for training

Section 6 Resource management--the requirements of resources for the quality management system, including the requirements for training

Section 7 Product realization--the requirements for products and services,

including contract review activities, purchasing activities, design and calibration Section 7 Product realization--the requirements for products and services,

including contract review activities, purchasing activities, design and calibration

Section 8 Measurement, analysis and improvement--the requirements for measurement activities, including customer satisfaction measures, data analysis and

continual improvement Section 8 Measurement, analysis and improvement--the requirements for measurement activities, including customer satisfaction measures, data analysis and

continual improvement

It's important to note that the revisions have affected six key documents in the ISO

9000 family: ISO 9001, ISO 9002, ISO 9003, ISO 9004, ISO 8402 and ISO 9000-1. ISO 9001, 9002 and 9003 are combined into one document--ISO

9001:2000. ISO 8402 vocabulary is now combined with the fundamentals and titled ISO 9000:2000. ISO 9004 has also been realigned with ISO 9001. These two

standards are considered a consistent pair and are intended to provide organizations with guidance to move beyond the basic requirements of ISO 9001.

As previously mentioned, the FDIS contains editorial changes (wording, etc.), and some paragraphs have been moved between sections. However, the intent of the

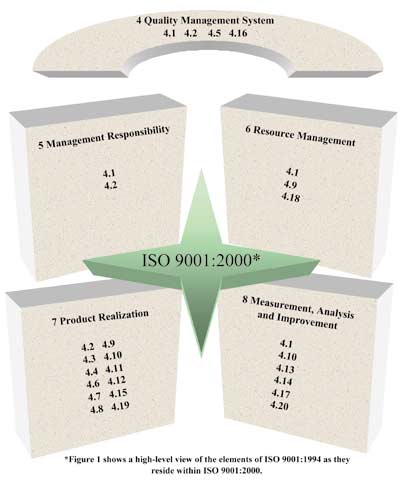

standard has not changed since the DIS was released. Figure 1 depicts how the elements of ISO 9001:1994 have been redistributed to the sections in ISO 9001:2000. Figure 1: ISO 9001:1994 Elements Within ISO 9001:2000

FDIS requirements at a glance In November 1999, The U.S. Technical Advisory Group (TAG) identified several

critical issues with the DIS. These included the absence of identification of measurement and test equipment and the exclusion of requirements for review and

disposition of nonconforming product. These issues were resolved at the Kyoto meeting and now have been added or clarified in the FDIS. The following

paragraphs provide a quick glance at the requirements found in each section of ISO 9001:2000.

Section 4 Quality management system This section provides the general requirements for the organization. While the

paragraphs for documentation control, records and the quality manual were moved from management responsibility in Section 5 of the DIS, the intent of the

requirements has not changed. The key requirements include:  Establishing, documenting, implementing, maintaining and continually improving the quality management system

Establishing, documenting, implementing, maintaining and continually improving the quality management system

Documenting a quality policy, objectives and quality manual Documenting a quality policy, objectives and quality manual

Implementing documentation required by the standard and documentation

required by the organization itself to ensure effective planning, operation and control of processes Implementing documentation required by the standard and documentation

required by the organization itself to ensure effective planning, operation and control of processes

Controlling the documentation Controlling the documentation

Establishing and maintaining records Establishing and maintaining records

Section 5 Management responsibility Top management will be required to take a more active role in the quality management system. Some editorial changes have occurred in the FDIS; however,

the intent remains the same as in the DIS. This section requires top management to:  Provide evidence of their commitment to the development, implementation and continual improvement of the effectiveness of the quality management system Provide evidence of their commitment to the development, implementation and continual improvement of the effectiveness of the quality management system

Ensure customer requirements are determined and fulfilled Ensure customer requirements are determined and fulfilled

Establish the quality policy and ensure it provides a framework for establishing and reviewing quality objectives

Establish the quality policy and ensure it provides a framework for establishing and reviewing quality objectives

Establish quality objectives at relevant functions and levels in the organization

and ensure that the objectives are measurable and consistent with the policy Establish quality objectives at relevant functions and levels in the organization

and ensure that the objectives are measurable and consistent with the policy

Perform planning activities for the quality management system Perform planning activities for the quality management system

Ensure the responsibilities, authorities and their interrelation are defined and communicated Ensure the responsibilities, authorities and their interrelation are defined and communicated

Appoint a management representative Appoint a management representative

Ensure that appropriate communication processes are established within the organization Ensure that appropriate communication processes are established within the organization

Conduct management reviews and demonstrate that decisions and actions are

taken regarding improvement activities Conduct management reviews and demonstrate that decisions and actions are

taken regarding improvement activities

Section 6 Resource management

This section requires that the organization determine and provide its resources for implementing, maintaining and continually improving the effectiveness of the quality

management system. It also requires that resources be determined and provided for addressing customer satisfaction. Some wording and title changes have occurred in

this section, but again, the intent of the DIS and the FDIS remains the same. Other requirements include:  Ensuring competency, awareness and training of employees, including evaluating the effectiveness of actions taken Ensuring competency, awareness and training of employees, including evaluating the effectiveness of actions taken

Ensuring that personnel are aware of the relevance and importance of their

activities and how they contribute to the achievement of the quality objectives Ensuring that personnel are aware of the relevance and importance of their

activities and how they contribute to the achievement of the quality objectives

Maintaining records of education training, skills and experience Maintaining records of education training, skills and experience

Identifying, providing and maintaining the infrastructure (facilities) needed to

achieve conforming product, including supporting services that imply activities such as transportation, communication and maintenance programs Identifying, providing and maintaining the infrastructure (facilities) needed to

achieve conforming product, including supporting services that imply activities such as transportation, communication and maintenance programs

Identifying and managing the factors of the work environment needed to achieve conforming product Identifying and managing the factors of the work environment needed to achieve conforming product

Section 7 Product realization

The deletion of the requirement for identification methods for inspection, measuring and test equipment in the DIS concerned the U.S. TAG. This issue has

since been resolved, and the requirement has been added to the FDIS. Also, two important clarifications to the FDIS include a note under 7.2 Customer-related

processes that makes provisions for situations such as Internet sales, where the requirement for a formal review may not be practical. The other clarification, found

under 7.6 Control of measuring and monitoring devices, specifies that computer software used for monitoring and measuring specified requirements must be

confirmed. Other wording and title changes, as well as renumbering of some of the subsections, can be found; however, as with the other sections, the intent remains

the same in the FDIS. Key requirements found in this section include: Planning and developing processes required for product realization  Customer-related processes including contract review and customer communication Customer-related processes including contract review and customer communication

Requirements for design and development of product including control of

changes Requirements for design and development of product including control of

changes

Purchasing requirements Purchasing requirements

Production and service provisions (process control including special processes)

Production and service provisions (process control including special processes)

Identification and traceability Identification and traceability

Control of customer property

Control of customer property

Preservation of product Preservation of product

Control of monitoring and measuring devices Control of monitoring and measuring devices

Section 8 Measurement, analysis and improvement

From a U.S. perspective, one of the more concerning issues was the change made to the DIS from the second committee draft in the section on nonconforming

product. This section had remained consistent with the 1994 version (4.13 Control of Nonconforming Product) until the DIS was published; then the requirements for

review and disposition of nonconforming product were absent. Many quality professionals felt the changes were too drastic and that the requirements for

disposition should be reconsidered. This issue was resolved in the FDIS, which more clearly defines the requirements for dealing with nonconforming product.

Another change made to Section 8 was the broadening of the internal auditing requirements to include auditing of the QMS as defined by the organization vs.

compliance to the standard itself. Other requirements in Section 8 include:  Planning and implementing the monitoring, measuring, analysis and continual improvement processes Planning and implementing the monitoring, measuring, analysis and continual improvement processes

Monitoring information relating to the customer as one of the measures of performance of the QMS Monitoring information relating to the customer as one of the measures of performance of the QMS

Conducting internal audits Conducting internal audits

Monitoring and measurement of processes Monitoring and measurement of processes

Monitoring and measurement of product Monitoring and measurement of product

Controlling nonconforming product Controlling nonconforming product

Analyzing data Analyzing data

Facilitating continual improvement Facilitating continual improvement

Corrective action Corrective action

Preventive action

Preventive action

As with the other sections, editorial changes and title changes to Section 8 have occurred with the FDIS; however, the intent remains the same.

Documentation requirements

In ISO 9001:2000, there are now only six specific areas that require documented procedures. These procedures, considered the core of the quality management system, are as follows:  4.2.3 Control of documents 4.2.3 Control of documents

4.2.4 Control of quality records 4.2.4 Control of quality records

8.2.2 Internal audit 8.2.2 Internal audit

8.3 Control of nonconforming product 8.3 Control of nonconforming product

8.5.2 Corrective action 8.5.2 Corrective action

8.5.3 Preventive action 8.5.3 Preventive action

The standard also requires that in order for the organization to carry out production and service activities under controlled conditions, it must consider the availability of

work instructions. For all other areas, it is up to the organization to determine what documentation it will need to ensure effective planning, operating and controlling of

its processes. This determination should be based on the size of the organization, type of activities, complexity of the processes and their interactions, as well as the

competence of the personnel. This flexibility with procedures will require organizations to think very carefully about their need for documentation. It will also

cause third-party auditors to audit people by asking for a demonstration of the effective control of processes and systems. Exclusions While many users pay little attention to the introductory paragraphs that describe

terms, scope and application, one paragraph requires special attention. Paragraph 1.2,63 Application, should be reviewed carefully because understanding the

exclusions will become important in defining the scope of registration. ISO has published a document to describe the criteria surrounding these exclusions in order

to clarify what can and cannot be excluded. Any company that has excluded requirements of the standard should read this document to become familiar with the

criteria. Exclusions may be made only to requirements found in Section 7 and must be explained in the quality manual to ensure that customers are not misled or

confused about the scope of an organization's quality management system. The organization must clearly define which of its products are to be included within the

scope of its QMS. Products that are included within this scope are expected to meet all of the requirements within ISO 9001:2000 unless it can be demonstrated

that certain requirements in Section 7 don't apply. Typical exclusions may include design if the company has no responsibility for the design or development of the

products it produces; customer property; identification and traceability; or control of monitoring and measuring devices, especially in the case of service organizations.

Exclusions that are not permissible include:  Failure to justify exclusions to Section 7 requirements in the quality manual

Failure to justify exclusions to Section 7 requirements in the quality manual

Failure to apply a requirement of Section 7 because it wasn't a requirement in the 1994 version and therefore was not previously included in the organization's QMS Failure to apply a requirement of Section 7 because it wasn't a requirement in the 1994 version and therefore was not previously included in the organization's QMS

Excluding of Section 7 requirements because they are not required by regulatory bodies and the requirements would affect the organization's ability to meet customer requirements

Excluding of Section 7 requirements because they are not required by regulatory bodies and the requirements would affect the organization's ability to meet customer requirements

Registrars will also want to ensure that the scope of an organization's certificate has been correctly defined because this information will appear on the certificate to

differentiate between organizations with design functions and those without. Upgrading to the revisions Compliance guidelines allowing 36 months after the formal release of the published standard have been provided to the registrar community. Many registrars are

encouraging organizations to upgrade to the revisions as quickly as possible. Much of the upgrading process will be coordinated with the surveillance visits for

companies that are already registered. The upgrades will not require organizations to have a complete systems audit, but rather an audit to review whether the modified

or new requirements have been incorporated into the existing quality management system. Organizations already registered will be able to renew their 1994 certificates

as they make the transition. Organizations pursuing registration will have the option of becoming registered to either the 1994 or 2000 versions during this three-year

timeframe. However, after the 36-month time allowance, 1994 certificates will no longer be considered valid, nor will new certificates be issued to the 1994 version.

Most registrars are in the process of contacting their customers with detailed timing information. If an organization has not heard from its registrar on this issue, it

should contact the registrar as soon as possible. In a nutshell

The standards are well on their way to release. Organizations should become as familiar with the changes as possible and not delay the process of upgrading their

systems. According to feedback from registered companies, the most challenging areas for organizations will be establishing measurements, incorporating a process

approach for business management, moving away from compliance-based thinking and gaining top management's involvement. Careful planning and successful

execution will be critical in achieving compliance to the new requirements as well as positioning the organization for continual improvement. About the authors Jeanne Ketola, CEO of Pathway Consulting Inc. in Minneapolis, Minnesota, has

more than 20 years of diverse business experience. She is an ASQ Certified Quality Auditor, an RAB Quality Systems Auditor and a trained management coach. Ketola

is an active participant of the U.S. TAG to TC 176, which is responsible for reviewing and writing the ISO 9000 revisions, establishing all U.S. positions and

voting on the final draft standard. She has participated at a national level in writing the auditing guidelines for ISO 9000-Q10011. E-mail her at jketola@qualitydigest.com .

Kathy Roberts, President of Sunrise Consulting Inc. in Raleigh, North Carolina, has held quality engineering and quality management positions in a variety of industries

during the past 10 years. She is an ASQ Certified Quality Auditor and a trained examiner for the North Carolina Performance Excellence Process. Roberts is an

active member of the U.S. TAG to TC 176. E-mail her at kroberts@qualitydigest.com .

Ketola and Roberts are authors of the book ISO 9001:2000 In a Nutshell: A Concise Guide to the Revisions, published by Paton Press. For more information about their book, visit www.patonpress.com, e-mail books@patonpress.com or call (530) 342-5480. |