Organizational Excellence--Part Four

H. James Harrington

jharrington@qualitydigest.com

This article is the fourth

in a five-part series on organizational excellence, which

comprises five elements. The first three, discussed in previous

columns, include process management, project management

and change management.

We live in a knowledge-based economy. Most organizations'

value is defined by their intellectual capital rather than

their physical assets. "The fundamental building material

of a modern corporation is knowledge," says Hewlett-Packard's

Valery Kanavsky. All organizations have it, but most don't

know what they know, don't use what they do know and don't

reuse the knowledge they have. In today's economy, knowledge

is power, and power brings success. Failure, survival or

success depends upon the way an organization uses its knowledge.

Knowledge management isn't new. During the 20th century,

knowledge importance expanded exponentially. Sixty years

ago, Winston Churchill stated, "The empires of the

future are empires of the mind." Forty years ago, Peter

Drucker talked about the "knowledge worker."

Today,

the news published in a single issue of The New York Times

represents more information than the average person accumulated

during a lifetime in the 17th century. During the 1950s,

organizations were searching for information; today they

and their employees are drowning in it. The little 15-inch

screen on my desk can display a thousand times the information

found in the books lining the dozen bookcases in my library.

The amount of information available to us doubles every

five years. We don't have time to absorb what's relevant

to our interests--let alone sort through the mountains of

existing data to find what's actually relevant. It's no

wonder that successful organizations have made learning

and applying knowledge a core competency. Today,

the news published in a single issue of The New York Times

represents more information than the average person accumulated

during a lifetime in the 17th century. During the 1950s,

organizations were searching for information; today they

and their employees are drowning in it. The little 15-inch

screen on my desk can display a thousand times the information

found in the books lining the dozen bookcases in my library.

The amount of information available to us doubles every

five years. We don't have time to absorb what's relevant

to our interests--let alone sort through the mountains of

existing data to find what's actually relevant. It's no

wonder that successful organizations have made learning

and applying knowledge a core competency.

Knowledge isn't like merchandise. Unlike a tangible product,

you can sell information, give it away or trade it, but

you'll still retain the knowledge. In fact, knowledge becomes

more valuable the more you use it. However, it's also perishable;

if it isn't renewed and replenished, it becomes worthless.

Yes, knowledge has a shelf life. It's always changing, and

this means that every organization must either become a

learning organization or become obsolete.

Knowledge comes in two forms: explicit and tacit. Explicit

knowledge includes information that's stored in semistructured

content such as documents, e-mail, voice mail or video media.

I call this "hard" or "tangible" knowledge.

It's conveyed from one person to another in a systematic

way. Tacit knowledge is information that's formed around

intangible factors resulting from an individual's experience.

It's personal and content-specific.

A knowledge management system is a proactive, systematic

process by which value is generated from intellectual or

knowledge-based assets and disseminated to stakeholders.

KM methodology was developed so that intellectual capital

could be managed as an organizational asset. It's designed

to capture and flow an organization's data, information

and knowledge and deliver them to the knowledge worker who

uses them on a day-to-day basis.

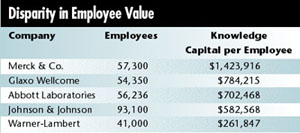

Paul A. Strassmann recently provided in Knowledge Management

magazine an insight into how knowledge capital per employee

translates into dollars:

During the past 50 years, the world economy has transitioned

from a production-based value system to being knowledge-based.

Our technological ability to capture data far outstrips

our ability to absorb it. A KMS helps an organization prepare

for constantly shifting demographics and customers' needs

by sorting through masses of data and providing the specific

information needed to solve and take advantage of business

opportunities.

Most of the problems facing organizations today can be

avoided if the company's innate knowledge is made available

to decision makers. As quality professionals, we must focus

our efforts on ensuring that everyone has the information

and skills to do his or her job error-free. Developing an

excellent KMS is the best way to accomplish this.

I recommend a six-phase approach made up of 61 activities.

Phase I--Requirements definition (seven activities)

Phase I--Requirements definition (seven activities)

Phase II--Infrastructure evaluation (16 activities)

Phase II--Infrastructure evaluation (16 activities)

Phase III--KMS design and development (12 activities)

Phase III--KMS design and development (12 activities)

Phase IV--Pilot program (15 activities)

Phase IV--Pilot program (15 activities)

Phase V--Deployment (10 activities)

Phase V--Deployment (10 activities)

Phase VI--Continuous improvement (one activity)

Phase VI--Continuous improvement (one activity)

Keep in mind that a successful KMS's most critical component

is the culture of the enterprise that's implementing it.

Without a culture dedicated to being the best, most business-focused,

employee-centric and customer-aware, any advantages provided

by a KMS will be largely wasted.

Knowledge management is about people, communication, networking,

and a knowledge-sharing and -creating culture. It's not

a prescriptive technological process.

One challenge to implementing a KMS lies in transforming

knowledge--including process and behavioral information--into

a consistent technological format that can be easily shared

with the organization's stakeholders. But the biggest obstacle

is changing the organization's culture from knowledge-hoarding

to knowledge-sharing.

Jerry Ash, a Forbes Group counselor, envisions the future

workplace as "an environment without cultural, political,

professional or structural boundaries, where workers and

managers at all levels can think together, drawing on the

rich and diverse backgrounds, training and work experience

previously confined to information silos and narrowly defined

jobs of the former Industrial Age."

H. James Harrington has more than 45 years of experience

as a quality professional and is the author of 20 books.

Visit his Web site at www.hjharrington.com.

Letters to the editor regarding this column can be sent

to letters@qualitydigest.com.

|