An Ounce of Prevention

"We've implemented both TQM and Six Sigma. We have a rainbow of Black, Yellow and Green Belts running around solving problems, and our records show that our service and product quality levels are better than they've ever been before. Why then is our customer-satisfaction level going down? Can it be that these quality programs aren't what our customers want? I guess they're all failures, and we need to look for another answer."

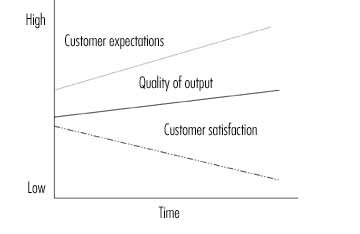

These are typical comments I hear from CEOs and plant managers around the world. It's becoming more common every day. How can TQM and Six Sigma produce negative results when they're designed to improve quality? The answer is that they're improving quality and saving costs, but that doesn't mean customer-satisfaction levels will rise unless your external customers are made aware of your internal quality improvements. Your product and service quality levels may be improving, but not at a rate equal to your customers' changing expectations, as the figure below illustrates.

Six Sigma Black Belts work on internal problems and find ways to save money. They're required to save a minimum of, let's say, $1 million per year, not improve customer satisfaction. Everyone focuses on measurements, and when the unit of measure is dollars saved, it's no longer a quality initiative but a cost-reduction program. It's the same old story: What's measured will be managed well, and what most organizations are trying hard to manage are costs.

Six Sigma has offered a lot of benefits in terms of cost reduction, but how much of that has been passed on to customers? Based upon the costs of products I buy, not much. When costs do come down, it's usually because the product is manufactured in Asia. Unfortunately, we can't improve customer satisfaction simply by reducing costs; we must improve the quality and reliability of our products and services as well. Based on my evaluation of data supplied by Consumer Reports and J.D. Power and Associates, our customers' expectations of our products are increasing at a rate of about 13 percent per year, and our product quality is improving at about 10 percent per year. The gap between what we deliver and what's required widens continuously. Our customers are becoming more dissatisfied.

To turn this around, we need a paradigm shift that will improve quality, not simply reduce cost, and we should produce improvements of 15 to 20 percent per year, not a meager 10 percent. It's time we started preventing errors rather than spending time solving problems. U.S. professionals are the best problem solvers in the world because we create more problems than anyone else and therefore get more practice. Measure the percentage of time your CEO spends on prevention vs. problem solving. I estimate it will be a ratio of one-to-three or higher.

Our great leaders of industry have gotten where they are because they're great problem solvers. They don't like to plan. It's almost un-American to read the assembly instructions for Johnny's bike; you only resort to the instructions as a last resort, when everything else fails. The great problem solvers at the top of our organizations think they should eventually pass the reins to someone like themselves--problem solvers. When I worked at IBM, the cynical joke was if you wanted to get ahead, you created a problem you could solve and solved it. As a result, the big boss rewarded you with a promotion.

We should think about problem solvers such as Black Belts as we do dentists: We wouldn't have to spend money on them if we just took the time to do what we should. But when we neglect our teeth, we need someone around to pull out the infected ones.

I'd like to propose the following paradigm: Focus on increasing what goes right for your customers, not on what goes wrong.

Lead or be led is the rule, and U.S. industries need to set the pace for the rest of the world, not continue to operate by cleaning up the messes we create.

H. James Harrington is CEO of the Harrington Institute Inc. and chairman of the board of Harrington Group. He has more than 55 years of experience as a quality professional and is the author of 22 books. Visit his Web site at www.harrington-institute.com.

|