| by Kennedy Smith

Baldrige Calendar

March 12--2004 eligibility packages due with

a nomination to the board of examiners

March 26--2004 examiners notified of selection

March 28-31--Quest for Excellence XVI Conference

April 13--2004 eligibility certification packages

due

May--Examiner training throughout the month

May 27--2004 award applications submitted on

paper due

June 2--Judges meeting

June 3--Judges/overseers meeting

July 15--2004 case study packet available on

the Web

July 26-27--State and local quality awards workshop

July 28--Improvement Day

July 29--Judges meeting

August-September--Consensus planning and consensus

calls

Oct. 17-23--Health care, service and small business

site visits

Oct. 24-30--Education and manufacturing site

visits

Nov. 5--2005 examiner applications due

Nov. 16-19--Judges meeting

Note: Award winners are typically announced

in December. As of printing, the date for the

2003 Baldrige Awards ceremony had not been set.

|

It’s the highest recognition

of quality in the United States. Some call it the Academy

Award for performance

excellence. Most just call it “The Baldrige.” Whatever

the nomenclature, it’s agreed that the Malcolm Baldrige

National Quality Award Program is not only beneficial to

individual organizations seeking excellence in quality,

and it’s also believed to boost the quality and economic

levels of the entire country.

Nonetheless, criticism of the program does exist. For

example, some think that as the criteria changes, its emphasis

leans too heavily on business results and not enough on

quality. Other challenges faced by Baldrige administrators

are the difficulties in proving that the Baldrige journey

does, in fact, reap measurable results.

The MBNQAP is named after former U.S. Secretary of State

Malcolm Baldrige, who held the position from 1981 until

his death following a rodeo accident in 1987. Baldrige

had a personal interest in quality management and improvement,

and helped design a draft of the award program before his

death. That year, Congress established the official award

program to recognize U.S. manufacturing and service organizations

of any size for their achievements in quality and named

it in his honor.

Until 1999, only manufacturing and service organizations

were eligible to apply for a Baldrige Award. During the

mid-1990s, award administrators developed criteria for

two new categories: education and health care.

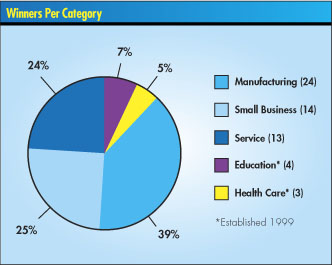

From 1988 to the present, 58 organizations have earned

Baldrige Awards, including 24 manufacturing organizations,

14 small businesses, 13 service companies, four educational

institutions and three health care organizations. (See

the figure below.)

Now there is a push to enable not-for-profit organizations

to apply for the award. In fact, the Miller-Hart bill,

H.R. 3389, an amendment to the original act that helped

establish the MBNQAP, is currently being pushed through

Congress. The amendment would add the words “nonprofit

organizations” to section 17(c)(1) of the Stevenson-Wylder

Technology Innovation act of 1980.

Chris Zabel, administrator of Bethel Lutheran Church

of Rochester, Minnesota, is looking forward to the inclusion

of the not-for-profit category. Bethel earned the Baldrige-based

Minnesota Quality Award in 2002. An evaluator with the

Minnesota Council for Quality, Zabel says that Bethel may

apply for the Baldrige Award, provided the criteria could

be tweaked to better suit the needs of nonprofit organizations.

Bethel has even had offers from organizations willing to

underwrite the entire process to see Bethel go for the

Baldrige Award.

The improvements Bethel is reaping from the infusion

of Baldrige-based quality are many. “Worship attendance

has gone up,” notes Zabel. “Financial support

has gone up; we’re able to give more to our local,

national and global benevolences. There’s a higher

level of satisfaction from our congregation and staff.”

Churches are just one type of organization currently

ineligible for the Baldrige Award. Other organizations

include government agencies at all levels, charitable organizations,

mutual insurance companies, credit unions and utility cooperatives.

With an expected influx of not-for-profits eyeing the

Baldrige, questions arise about changes in the award criteria.

“We would not create a new set of criteria for not-for-profit

organizations,” explains Harry Hertz, director of

the MBNQAP. “We would actually make modifications

to the business criteria overall to make some of the language

more friendly across sectors.” The reasoning behind

this decision is that not-for-profits include such a heterogeneous

mix that developing separate criteria would be more confusing

than simply tweaking the already developed

criteria, Hertz says.

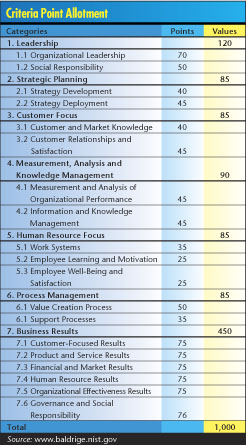

The Baldrige criteria consist of seven key indicators

of success. Winners are selected on a 1,000-point scale

for their achievements in all categories, so if one indicator

is lacking, the chances of winning a Baldrige decreases.

The criteria include:

Leadership. This category takes a look at how top management

guides the organization toward best practices. Leadership. This category takes a look at how top management

guides the organization toward best practices.

Strategic

planning. The organization must set strategic

goals toward excellence and determine action plans. Strategic

planning. The organization must set strategic

goals toward excellence and determine action plans.

Customer

and market focus. This criterion examines how

customers and markets are acquired, satisfied and retained. Customer

and market focus. This criterion examines how

customers and markets are acquired, satisfied and retained.

Measurement,

analysis and knowledge management. The

organization must show effective management, use, analysis,

and improvement of data and information to support its

processes and performance management system. Measurement,

analysis and knowledge management. The

organization must show effective management, use, analysis,

and improvement of data and information to support its

processes and performance management system.

Human

resource focus. How does the organization empower

and retain its workforce? Human

resource focus. How does the organization empower

and retain its workforce?

Process

management. The organization must effectively design, manage,

and improve its production/delivery and support processes. Process

management. The organization must effectively design, manage,

and improve its production/delivery and support processes.

Business

results. This category studies the ways in

which the organization performs against competitors. It

examines performance in all key business areas, including

customer satisfaction, financial and marketplace performance,

human resources, partner performance, operational performance,

governance and social responsibility. Business

results. This category studies the ways in

which the organization performs against competitors. It

examines performance in all key business areas, including

customer satisfaction, financial and marketplace performance,

human resources, partner performance, operational performance,

governance and social responsibility.

Since their inception, the Baldrige criteria have been

in a constant state of evolution, adapting to changes within

the business climate. “We go through an annual improvement

process that begins with studying what’s going on

in the business, education and health care communities

to understand their most important leading-edge challenges

and approaches to improvement,” explains Hertz.

This process is followed by a solicitation of feedback

from focus groups, Baldrige Award winners and those going

through the award process. “Then a first draft of

the next year’s criteria and any changes to process

is developed and goes out to all of our judges, overseers

and other contributors to see if we got it right from their

perspective,” Hertz continues. “Based on that,

the second and final draft is generated, which becomes

the criteria for the next year.”

For example, in 2003, the issue of ethics was brought

into the criteria after a string of companies made headlines

for disreputable business tactics. This was an area not

previously addressed in the criteria.

One important factor in utilizing the Baldrige criteria

set is that it fits with other quality improvement initiatives,

meaning that an organization doesn’t have to overhaul

its entire quality system in order to become eligible for

the award. In other words, organizations don’t have

to choose between their management system and the MBNQAP.

Examples of Baldrige winners using well-known quality

methodologies include 1993 recipient Eastman Chemical Co.,

which has used ISO 9000 for more than a decade; 1988 and

2002 winner Motorola Inc., a pioneer of the Six Sigma methodology;

SSM Health Care, the first health care recipient, which

utilizes its own method called continuous quality improvement;

and 1999 recipient STMicroelectronics Inc., which conforms

to ISO quality standards, Six Sigma and Baldrige criteria.

Once an organization decides to embark upon the Baldrige

journey, the ride doesn’t stop at the application

process. From an improvement standpoint, applying for the

Baldrige Award would be useless if the company didn’t

gain new knowledge from it. Therefore, organizations that

do apply receive

extensive feedback reports from Baldrige examiners.

Lauded as one of the most useful tools garnered from

the Baldrige journey, feedback reports suggest areas for

improvement and can be used to gauge new directions in

quality enhancement. In fact, it’s rare for Baldrige

Award recipients to receive the accolade on their first

try. Typically, they go through a process of receiving

feedback reports, making improvements and reapplying until

the highest honor is achieved.

When an organization receives the Baldrige Award, the

journey doesn’t end there. Recipients are asked to

participate in several forums to share their experiences

and best practices. “It’s wonderful that the

Baldrige requires companies to do a show-and-tell and make

public presentations,” comments Richard Schonberger,

president of Schonberger and Associates, a performance

management consulting firm. “Most companies don’t

know what’s going on and don’t have good probes

into the outside world to find out what their competitors

are doing and what their customers care about. Sharing

best practices is the best way to learn these things.”

One of the most valuable tactics to ensure a successful

Baldrige journey is to become an examiner. The MBNQAP doesn’t

deem applicants becoming examiners a conflict of interest;

rather, doing so is considered almost essential for fully

understating the process. However, precautions are taken

to avoid any appearance of conflicts of interest; examiners

are required to disclose all business affiliations that

might create an atmosphere of subjectivity. And, it’s

a violation of the code of conduct for board members to

inquire about applications other than those to which they’re

assigned.

The most obvious advantage of becoming an examiner while

going through the application process is that applicants

know what they are in for.

Although Schonberger gives great praise to the MBNQAP,

he says the criteria are too focused on business results

and not focused enough on quality. As it stands, the customer

and market

focus category counts for 450 of the criteria’s possible

1,000 points.

“The category of business results shouldn’t

be in the criteria at all,” he argues. “Of

course we want a quality award to be given to companies

that are successful in business, but that’s mixing

means and ends. It gives the impression that organizations

aren’t sure that quality is the right thing to do,

so they have to prove it with financial results. It reflects

a basic doubt that quality really works.”

Although Schonberger believes the criteria’s evolution

is causing instability and an overall drift from quality

management, he is pleased with some recent changes. For

example, he’s glad to see the “business process” portion

of the process management criterion eliminated. “Although

the process management category only accounts for 85 of

1,000 points, getting rid of business process requirements

helps companies focus purely on quality.”

Another

change he applauds is the weight of item 7.1, customer-focused

results, which counts for 75 points. Financial

and market results also count for 75 points, which Schonberger

says is a step in the right direction. Another

change he applauds is the weight of item 7.1, customer-focused

results, which counts for 75 points. Financial

and market results also count for 75 points, which Schonberger

says is a step in the right direction.

“One criticism that’s hard to respond to

is: ‘Prove that Baldrige is so good. Give us an across-the-board

metric or index that shows that Baldrige Award recipients

outperform other organizations,’” adds Hertz. “We

struggle with trying to develop such a metric that would

combine financial performance, customer satisfaction and

internal operational success.” The idea of creating

such a metric is challenging, particularly because every

organization has different ways of measuring their successes.

The only existing comparative study is the Baldrige Index,

a fictitious portfolio of stocks from publicly traded Baldrige

Award recipients, which is pitted against the Standard

and Poor’s 500. “The

problem with that index--and we knew this was a problem

from the start--is that it only represents a small fraction

of Baldrige Award recipients,” explains Hertz. Privately

held organizations aren’t included, and divisions

of larger corporations must be weighted differently.

Another criticism Hertz has witnessed involves former

Baldrige Award recipients that are no longer performing

as role models. “We have no ongoing monitoring of

former recipients of the Baldrige Award, and they have

no requirement to not change management or continue to

follow Baldrige,” he says. “Obviously we hope

they will continue, but management changes, times change

and organizations change.”

Yet another challenge that former Baldrige Award recipients

encounter is keeping their workforce committed to Baldrige.

As Hertz mentioned, companies, employees, top management

and economics change over time, all making it difficult

to keep the Baldrige journey a top priority. One example

of a company that strives to stay on the Baldrige path

is Motorola. This pioneer of the Six Sigma methodology

was one of the first Baldrige Award winners in 1998, and

they won again in 2002. “Keeping our eyes on the

Baldrige journey is difficult when other immediate crises

may come up,” he admits. “It’s a challenge

of staying the course.”

Although some companies that have received Baldrige Awards

in the past still believe that it’s a powerful tool

toward performance excellence, they don’t continue to utilize

the criteria as their primary method for quality improvement.

More so, many former Baldrige Award winners don’t

wish to apply again. Rather, they originally used the criteria

as a way to organize and evaluate the status of their companies’ processes,

not to win the award.

For example, Ames Rubber Co., a 1993 recipient in the

small business category, uses an amalgam of processes to

create a world-class system. According to a Baldrige CEO

Issue Sheet, Tim Maril, CEO of Ames, says the Baldrige

journey is only one step in his company’s quality goals. “Each

organization has to choose what best serves its needs,

but for success, they all require a commitment of resources.”

The Baldrige criteria are highly regarded within the

United States, as evidenced by the fact that many state

quality award programs mirror the MBNQAP. “We have

a network of state and local programs,” says Hertz. “We

bring them together once a year for a workshop to share

information with them and for them to share information

with each other. As far as I know, all U.S. state and local

programs are now Baldrige-based to some extent.”

On a global scale, the MBNQAP stays connected to other

countries’ excellence awards through the Global Excellence

Model Network. Comprising leaders from award programs around

the world, members of the GEM Network meet once every 12

to 18 months to benchmark one another’s programs.

The MBNQAP is also part of the European Foundation for

Quality Management, which administers the European Quality

Award, and is connected to quality awards in Japan, Australia,

South Africa, India and Singapore.

Because the BNQAP focuses so much on sharing best practices,

a prime resource for learning more about the program is

its own Web site, www.baldrige.nist.gov. The

site contains self-assessments, a schedule of events, applications,

news and frequently asked questions.

Kennedy Smith is Quality Digest’s associate

editor.

To read Richard Schonberger’s article “Is

the Baldrige Award Still About Quality?” refer to

the December 2001 issue of Quality Digest, which can be

found through an archive search at www.qualitydigest.com.

|