by Navdeep S. Sodhi

In a technical context, the word “quality” can have two meanings, according to the American Society for Quality: “1. The characteristics of a product or service that bear on its ability to satisfy stated or implied needs; 2. A product or service free of deficiencies.”

An important characteristic of a product or service is a price that satisfies the implied need for profitability, at least from top management’s viewpoint.

Just as quality in manufacturing became important in Detroit during the 1970s with the oil crisis and increased competition from Japan, so is quality in pricing becoming important in many industries as the costs of raw materials skyrocket, the U.S. dollar plunges against other currencies, and companies face stiff competition worldwide. The difference now is that, for many companies, the tool set for implementing and deploying quality initiatives in manufacturing is quite sophisticated. What’s lacking is a means for targeting and adapting this tool set for pricing.

This article describes a situation faced by a real company--we’ll call it Acme Industries Inc.--in which it was compelled to adapt its Six Sigma manufacturing expertise to improve its pricing processes. The result was Six Sigma pricing, previously described in a May 2005 article in the Harvard Business Review and more thoroughly in my book Six Sigma Pricing: Improving Pricing Operations to Increase Profits, (FT Press, 2008).

Executives at Acme Industries Inc., an industrial manufacturer, called an emergency planning session. Unless they could improve profits within one or two quarters, the company’s projections to Wall Street regarding profits would seem foolishly optimistic. To increase profits, the company had already cut costs as much as possible. Now it would have to increase prices without losing sales. The question was how to do that given the competition and the company’s own erratic history.

In the past, the company aggressively pursued market share by allowing sales representatives a lot of flexibility on price. However, Acme’s dollar sales grew only marginally in a bullish market while profit plummeted. The following year, drastic inflation in critical raw materials motivated the company to push for higher prices, even if it meant losing some business. The company’s dollar sales remained flat. Operating profit grew by more than 10 percent, but the stock price remained below expectations and precipitated changes in key management positions. The new leaders reverted to capturing market share through lower prices, even though the costs of raw materials were rising. Annual results were dismal--sales, operating profit, and stock price were down.

Acme had its share of internal issues as well. These were due to the complexity of its manufacturing processes, as well as several pricing functions that contributed to price leaks. The functions included marketing, sales, finance, and pricing. Marketing owned pricing strategy, sales was responsible for fixing the customer’s price, and finance was responsible for all reporting. The different incentives in different functions led to variations on basic processes, shortcuts, double approvals, and a “buddy system,” even in the same product line and sales region. When someone tried to lead a discussion on price improvement, it degenerated quickly into a “blamestorm” rather than a brainstorm.

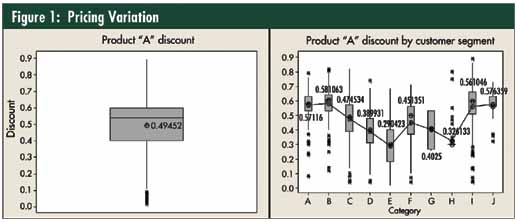

During the emergency meeting, the vice presidents of marketing and sales emphasized the tough external environment and the importance of pricing. The pricing manager showed two slides (see figure 1, below) that reflected the wide variation in discounts--from 5 percent to 95 percent--offered to customers within a single stock-keeping unit (SKU), regardless of the customer’s size or even the transaction.

Senior managers began to understand that this variability was a problem and symptomatic of process issues. Acme had enjoyed considerable success in reducing manufacturing variability by applying Six Sigma. The managers felt that the transaction- pricing process was similar enough to a manufacturing process to warrant piloting a Six Sigma pricing project in one of the company’s North American subsidiaries. They appointed the manager from pricing to carry out the five Six Sigma DMAIC steps: define, measure, analyze, improve, and control, with the help of a Master Black Belt recruited from manufacturing. The project sponsor was the senior executive responsible for pricing.

The project sponsor limited the scope to one particular product line. Acme’s project manager proposed that a defect be defined as a transaction invoiced at a price lower than the one that pricing had approved (or lower than the current blanket guidelines, when approval hadn’t been sought). The project would have to deliver a better understanding of the existing pricing process and a modified process to improve and control final transaction prices or discounts.

The project manager then enlisted people from pricing, finance, marketing, IT, and sales for the Six Sigma team. He also asked people in positions of influence at Acme to serve on a steering committee chaired by the project sponsor. These included the director of sales, vice president of IT, vice president of finance, and vice president of marketing. The committee confirmed the proposed problem definition and project charter, and set a project goal of increasing revenues by $500,000 during the first year following implementation--without incurring any losses in market share or unit sales volumes.

The project manager formally interviewed colleagues from IT, sales, pricing, finance, and marketing. He also sought informal feedback from other people in these functions to draw a high-level diagram of the entire process showing information flow from one step to the next. The map revealed a pricing process with six main steps. In practice, however, the sequence was replete with exceptions and shortcuts.

• Step 1: Perform initial price assessment with customer. The input for this are the list price, the blanket-discount guidelines for sales in the particular market, and the customer’s product and pricing requirements. The output is a discount taken off the list price. Approval is needed from pricing if the discount is deeper than the maximum authorized for the particular market.

• Step 2: Request pricing approval. For pricing personnel receiving such a request, the input are the price the sales rep has requested and the guidelines for pricing analysts. In practice, sometimes a sales rep offered a final discounted price to the customer without prior approval.

• Step 3: Compile quotation information. The input are the information about the customer and the order provided by the sales rep to support his or her request. The output are the complete details of the transaction. In practice, the sales rep didn’t or couldn’t provide enough information about the quotation.

• Step 4: Review and analyze quote. Input are the completed quotation information generated in the previous steps, including the tentative price that the sales rep requested, reports summarizing the history of similar transactions in the particular market, and, when available, reports of similar transactions with the same customer. In practice, with information scattered in different computer systems, the guidelines available to the pricing analyst could be quite poor, or the sales rep might request a quick turnaround, leaving little time for a pricing analyst to carry out this step effectively.

• Step 5: Communicate approval to sales office. The input are the tentative approved price from the analysis in the previous step and any additional information regarding the order and the customer. The output is the approved price. In practice, this could be the beginning of a prolonged negotiation between sales and pricing. A senior sales or marketing manager might weigh in at this point as well, and the final approved price could end up quite a bit lower.

• Step 6: Submit price to customer. The input is the approved price. The output is the tentative price for invoicing that the sales rep submits to the customer. In practice, the price that the sales rep actually offered to the customer could be quite a bit lower than the approved price.

The team also assessed the quality of the input data that supported the pricing process and found the sales transaction data to be reliable.

The team, with the help of the Master Black Belt, used a cause-and-effect matrix to guide discussion toward identifying and prioritizing problems. The main findings from this exercise suggested that the defects arose largely from problems in steps 1, 4, and 6, and from failures in reporting.

• Step 1. The team found that sales reps’ abilities to help customers select the right products and features was critical to managing customers’ price expectations. Unfortunately, salespeople’s failures in assessing customer requirements couldn’t be easily detected or controlled.

• Step 4. Sales reps sometimes wanted discount approval within hours of forwarding a request, which made it difficult for pricing analysts to determine whether the discount was reasonable.

• Step 6. Sales reps sometimes offered final prices to customers without prior approval, leaving pricing with little choice but to approve the price after the fact.

At the reporting stage, information about transactions wasn’t gathered or presented consistently. Discrepancies and redundancies in reports led to variability in the decisions the analysts made when deciding prices.

The project manager statistically analyzed transaction- level data for all transactions that occurred during the two years before the project started. He found the actual discounts to be bell-shaped in distribution. Using analysis of variance, he was able to conclude that different pricing guidelines had to be set for different transaction sizes and for different territories within the same market, and possibly even for customer groups.

Response speed was critical for salespeople to act quickly and close deals, but this was a challenge for pricing personnel. The project team concluded that clear guidelines were needed when granting deeper-than-usual discounts. The team proposed giving graduated discount-approval authority to individuals in three levels of the organization’s hierarchy: sales reps or managers, pricing analysts, and the pricing manager. Making the guidelines and the escalation process clear sped up the transaction process.

In cases where sales reps had already offered a customer a price and needed after-the-fact authorization, a new process required that the rep involve her boss for approval. The price already offered would still be honored, but now representatives could be held more accountable for making unauthorized commitments. Exception codes enabled Acme to track the reasons for price variations and made it clear who had been involved in the decision to deviate from guidelines.

Acme set up a monthly review during which executives--mainly the vice presidents of marketing, sales, and finance, along with their direct reports--looked at the company’s overall performance as well as particular geographic markets and transaction sizes. They determined whether the new process resulted in higher average transaction prices, fewer exceptions, and no loss in market share. If prices were under control but the company was still losing market share, then they needed to review pricing guidelines. The review team also checked exception codes to see who was deviating from the process.

The initial goal of generating $500,000 in incremental revenues during the first year was handily exceeded in only three months. More important, a subsequent across-the-board list-price increase was fully reflected in the top line for this product. By contrast, other product lines realized less than half the increase. That list-price increase, together with the tighter controls the Six Sigma team developed and implemented, resulted in $5.8 million in incremental sales in just the first six months following the project’s implementation, all going straight to the bottom line.

From an organizational perspective, the Six Sigma approach has considerably reduced the friction inherent in the pricing-sales relationship. Systematically collecting and analyzing price transaction data gave pricing analysts hard evidence to counter the more intuitively based claims that the sales staff had typically advanced in negotiating discounts. A frequent claim, for instance, was, “My customers want just as high of a percentage discount for a $1,000 transaction as they would get for one of $100,000.” Now that pricing knows that Acme’s customers tend to accept lesser discounts on lower-priced transactions, and that some customers are willing to pay higher prices, analysts can more easily push back when negotiating price approvals with sales personnel. They can respond confidently and authoritatively when sales reps ask, “Why is my authorized price higher than those in another market?” or “Why don’t we authorize the same price for all customers?”

Salespeople, for their part, are less likely to feel that the negotiation with pricing is driven by political motives or by personal desires to assert control. Moreover, they can use the same data to press their own points. It became clear, for example, that some sales offices that had been under scrutiny for aggressive pricing practices had, in fact, been acting reasonably given their local market conditions.

In light of the project’s success and its low cost, Acme is rolling out Six Sigma pricing across the organization.

Other companies operating in competitive environments can also benefit from Acme’s experience as they look for ways to exercise price control without alienating customers. They can transform the tenor of the relationship between their pricing and sales staffs from adversity to relative harmony by giving them a process for making joint decisions that are aligned with company objectives and based on solid data and analysis.

This success story doesn’t fully reflect the challenges of applying Six Sigma to pricing. Pricing processes have many stakeholders, which means that you’re treading on eggshells despite top management support. Not all of these stakeholders will perceive a Six Sigma pricing project as a win-win situation, even if it adds significantly to the company’s bottom line. This makes such a project vulnerable to sabotage at the first possible opportunity. Moreover, some of the key customers for pricing are internal, and their requirements may not be clearly stated. Additionally, pricing processes, when they do exist formally, are notable mainly for the lack of discipline or the effort required to follow them. Therefore, Six Sigma tools, such as failure mode and effects analysis, are critical in a successful control plan.

Still, relative to the effort that goes into the project, the increase in profits from applying Six Sigma or other quality-based approaches to pricing projects are huge in comparison to those brought by manufacturing or services projects.

Navdeep S. Sodhi is a pricing practitioner and thought leader with 12 years of global pricing experience spanning the airline, medical device, and manufacturing industries. He has an MBA from Georgetown University. He has applied Six Sigma and lean methods to pricing in his work for industrial manufacturers and is the recipient of the Award of Excellence from the Professional Pricing Society. His articles on pricing have appeared in the Harvard Business Review and the Journal of Professional Pricing. He serves on the board of The Business Marketing Association as the vice president of pricing thought leadership. He is also the co-author of Six Sigma Pricing: Improving Pricing Operations to Increase Profits (FT Press, 2008) .

|