Simsack’s Fishy Response

To everyone’s surprise

but Hartford Simsack’s, he’s been invited to

be a guest lecturer at his local community college. He was

recommended for the position by his mentor, Professor Stan

Deviation. Although he’s nearly given up on Simsack

becoming a competent statistician, Deviation hopes that

his student will master the subject if he, in turn, has

an opportunity to teach it.

Simsack, who fails in his attempts to secure the title

“professor” for his new venture, nonetheless

forges ahead with plans for his first lesson. Of course

he must take several days off from his position at Greer

Grate & Gate because class preparation is so demanding.

He decides that he’ll begin with basic data analysis

to warm up his students and let them experience his own

wisdom firsthand.

“Three ways of looking at data are through the concepts

of central location, shape and variability,” Simsack

drones. He notices that several students seem intent on

his lecture, recording every word on their PDAs. Occasionally,

their serious concentration is punctuated by beeps and trills,

but Simsack assumes that the noises are generated by overloading

their systems with formulas.

Emboldened, Simsack moves next to the concept of control

charts, leading the class through an exercise on creating

X-bar and R charts. A student raises her hand to ask a question--always

a dangerous moment for Simsack, who only skates on the surface

of understanding these concepts himself. She asks about

Ishikawa diagrams, which are used by colleagues at her part-time

job with a local hospital.

Because Simsack has never heard of Ishikawa diagrams,

he has no idea what she’s talking about. Never at

a loss, however, he recovers his composure by defining the

Taguchi loss function instead. That’s the only statistical

concept he knows with a Japanese name, and he assumes they

must be related.

“That’s a complex statistical methodology

used to measure costs when you’re off target,”

he tells the student confidently. (Simsack is known for

his confident attitude.)

Is Simsack himself off-target? Or did he happen to score

a bull’s-eye accidentally with his definition?

a) Amazingly, he’s managed to identify the Ishikawa

diagram without ever seeing one.

b) Sorry, Simsack. The only thing Taguchi and Ishikawa

have in common is that they’re both named after Japanese

statisticians.

The correct answer is b. Simsack is wrong again.

Taguchi is known for his work on the loss function that

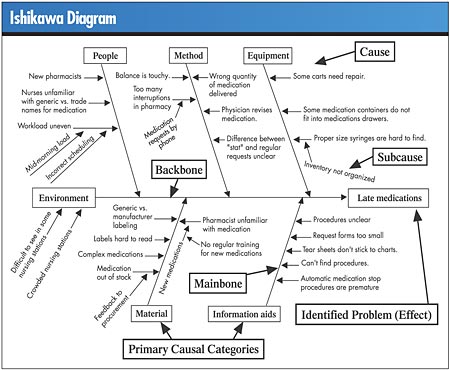

first gained recognition during the 1980s. The Ishikawa

diagram is more commonly referred to as a “fishbone”

or cause-and-effect diagram. It was developed in 1943 by

Professor Kaoru Ishikawa, president of the Musachi Institute

of Technology in Tokyo.

The Ishikawa diagram is an excellent tool to apply to

problem solving. For example, in the chart above, the problem

for a hospital pharmacy is identified as “late medications.”

Brainstorming has elicited possible causes for this problem,

recorded on appropriate “bones” or categories.

The next step involves looking for the most likely cause(s),

and then collecting data about the current situation with

respect to that cause.

Simsack might consider an Ishikawa diagram as he analyzes

problems associated with his lecturing.

Michael J. Cleary, Ph.D., founder and president of

PQ Systems Inc. is a noted authority in the field of quality

management and a professor emeritus of management science

at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. A 29-year professorship

in management science has enabled him to conduct extensive

research and garner valuable experience in expanding quality

management methods. He has published articles on quality

management and statistical process control in a variety

of academic and professional journals.

|