| by Derrell S. James

In the August edition of Quality Digest, I suggested a 12-step process for transforming businesses by using a combination of lean and Six Sigma philosophies and tools (“Six Sigma and Supply Chain Excellence”). Through the six lessons discussed in this article, I’ll provide insights into how smaller companies can apply these techniques.

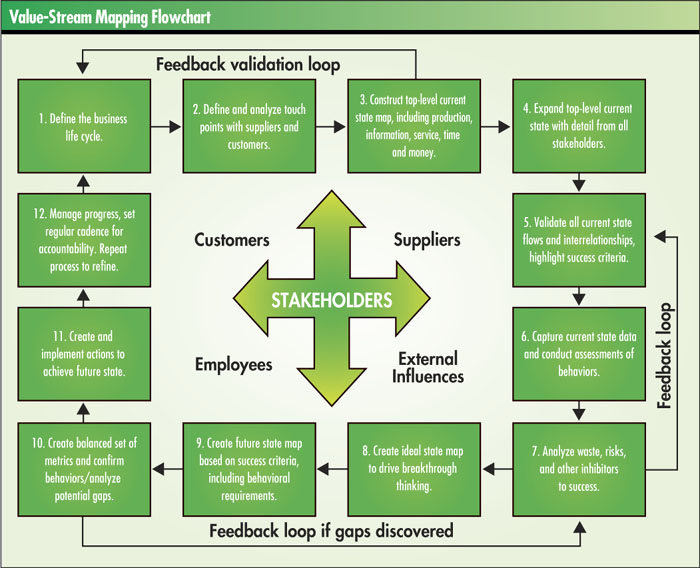

The figure on the following page shows a rather simple view of transforming a corporate life cycle value stream. Simplicity notwithstanding, the model suggests numerous opportunities for finding and eliminating waste, joining social and technical interactions, and ensuring value to stakeholders. With their limited infrastructures, small companies face additional challenges related to scope, cost and resources. Accordingly, we’ll examine some of the socio-technical lessons learned from applying the 12 steps, particularly how a small company can prosper using a large company’s customer-intimate techniques--without the infrastructure costs and political pressures incumbent in bigger corporations.

Often, organizations think their mission is to deliver a specific product or service. For example, a company that provides calibration services might believe its business involves repairing, measuring, and/or adjusting specific electrical or mechanical parameters of a specific device. Understanding a company’s true purpose, however, goes well beyond that. One must analyze the expected values demanded by customers, the processes within the company and between itself and its customers, and the channels available to deliver those values. Without the necessary infrastructure and overhead to perform this analysis, smaller companies often lack such a social-technical intimacy.

Given these parameters for determining a company’s “true” business, isn’t it more logical for the calibration company cited above to define its mission as delivering process readiness to its customers? In other words, performing the service is the means to the end, not the end itself. Smaller companies must not think in terms of strategy and tactics, but in terms of relationships. The calibration company would want to analyze the specific actions valued by its customers and expand its portfolio to include those products or services that would ensure the readiness of those actions. Calibration ensures that a customer’s equipment is functioning nominally when compared to an acceptable standard. However, a customer might also want to ensure that the equipment is available at the point of use in its facility, and that contingencies are prepared in the event of failure (e.g., an exchangeable unit, spare or on-demand repair service). Perhaps the customer also wants to measure the equipment’s effectiveness and thus requires process metrics or statistical data generated by the equipment in a usable format.

A company that limits itself to a specific product or service loses the flexibility needed for potential change or expansion in its work scope. It also loses the traction needed to ensure repeat business.

Where’s the rub? This is a simple question that most small companies tend to overlook, especially when working with larger customers. One-to-one relationships aren’t always possible, and this introduces a level of friction that can keep a company from delivering the best value to its customer--and best profits to itself. A thoughtfully developed value-stream map can identify the interactions of the processes’ stakeholders. This is called social-stream mapping and ensures that potential causes for friction are analyzed prior to initiating the relationship.

Interviews between customer and supplier are necessary to ensure all required data, analysis, follow-up and corrective action processes are identified--and all derived from effective decision making. Using cause-and-effect diagrams helps identify the potential friction between personnel, processes, parts and performance. It doesn’t take a long time or extensive resources to perform this analysis. Done properly, it ensures that potential problems are identified and pre-emptive countermeasures prepared.

Using standard value-stream mapping, it’s easy to pinpoint waste in material and information flows. However, unless they’re specifically analyzed, it’s not as easy to evaluate potential wastes in a customer’s or supplier’s psyche. By that I mean the personality of the contract and the interactions of the people producing, delivering and servicing it. Particularly true for small companies, nothing is more important than understanding this combination of performance and relationships. The contract, after all, is what ensures a company’s longevity and growth.

To identify these types of wastes, other social analysis techniques will prove effective. To a customer, value doesn’t mean simply demonstrating that your products or services are worth purchasing. You must also analyze workforce issues that might inhibit the installation, effectiveness and readiness of the customer’s processes. In the first lesson, we used the example of a company whose true business is process readiness. If that company neglects to review every aspect of how that readiness is realized, wastes will creep in and fester, thereby reducing the chances of a long-lasting relationship with a satisfied customer.

Your company should evaluate the state of your customer’s workforce. Does it have special requirements? Have there been recent layoffs? Have job responsibilities shifted that might place your company in an adversarial light? Within your own company, the people who install your product or deliver your service will probably meet face-to-face with those who actually use the product or service. Make the most of this golden risk-management opportunity by addressing any potential risks for “psychic waste.”

Similar to understanding a customer’s psyche, small companies must make a critical assessment of their own abilities to think and act in customer-acceptable terms. Because every customer is different, every solution must be tailored to that customer’s specific needs. This means your company’s products and services must be flexible enough to adapt.

Once a small company has identified its customer’s success criteria, it can then create the work instructions, metrics and management techniques that will generate that success. For example, with our process readiness company, the people interacting with customers will do so based on a specific description of acceptable behaviors and actions, approved by the customer and discussed at regular performance review meetings. These reviews must be established to ensure that behaviors match customer expectations. For a small company, this is essential to ensure longevity, opportunities for growth and expansion, and to create strong references to help capture future orders with other customers.

For a large company, reputation is a heavy coat: warm, comfortable, consistent and protective against difficult environments. For the small company, reputation is more like a diaphanous veil: thin, transparent and ineffective against the demands of a larger customer. However, customer skepticism isn’t necessarily due to a company’s size but rather to its lack of advanced process management caused by a limited staff or budget.

How can a small company overcome this disadvantage? First, the company must embrace the axiom that “all things measured improve.” With input from its customer, it must create a balanced scorecard of metrics to drive the processes necessary for successfully executing the contract. The scorecard’s “balanced” qualifier requires the company to create and analyze definitions of success--keeping in mind while doing so that human nature will always default to the minimum effort necessary to ward off trouble.

For example, a common metric in contracts is average turnaround time, also known as delivery cycle time. By implementing a balancing metric to reduce the variation of turnaround time--for example, percent of units shipped within three days--you can reduce the prospect that an unhappy customer will receive your product at haphazard and unpredictable delivery times. Remember, averages without a balancing, variation-reducing requirement will not only create waste but also those friction points discussed in lesson two.

Most companies will state with pride that they employ the best people in the industry and claim that their world-class processes ensure total customer satisfaction. If both of these statements were true, those companies not only would dominate the market but also monopolize it. Let’s be honest: No company is perfect, no relationship is perfect and no product or service performs perfectly.

A mature company recognizes that its true goal is the drive toward perfection. Actually achieving this perfect state is impossible. This final lesson is basic to James P. Womack and Daniel T. Jones’ theory of lean thinking. Maturity isn’t the culmination of 100 years of existence, a workforce with an average of 30 years’ experience or the highest investment in research and development. Rather, it’s a characteristic that can’t be bought or sold; it can only be achieved through a thoughtful orchestration of relationships, goals and metrics. Regardless of whether it implements lean, Six Sigma or another continuous improvement methodology, a small company is most likely to succeed if it stays focused on a quick ascent toward maturity. Keeping these six lessons in mind along the way will speed the journey and ensure success at the end.

Derrell S. James is the general manager of Sypris Test and Measurement’s calibration division. He has 15 years of experience in operations leadership and business development in high-technology manufacturing and service industries. James is a frequent speaker and writer on leadership, lean and continuous improvement, and operational effectiveness.

Sypris Test and Measurement is a leading provider of calibration services, test and measurement services, and specialty products to major corporations and government agencies. Sypris’ nationwide network of state-of-the-art fixed and mobile calibration laboratories are certified by A2LA for ISO/IEC 17025 and are also ISO 9001-registered. Visit www.calibration.com or www.sypris.com for more information.

|