| by Kennedy Smith

Software bugs cost the U.S. economy an estimated $59.5

billion each year, and more than half of that cost is shouldered

by the end-user, according to a 2002 study from the National

Institute of Standards and Technology.

The cost of failed projects for the U.S. information technology

industry in 2000 was estimated at $84 billion, reports The

Boston Globe.

| Founded in 1976 by James H. Goodnight,

SAS (www.sas.com) develops business intelligence software

that serves more than 40,000 businesses, government

agencies and educational organizations in 118 countries.

Among other awards, SAS was chosen as one of FORTUNE

magazine's "100 Best Companies to Work for in

America" in 2003.

In the following interview, Cynthia Morris, SAS's

research and development director in charge of software

quality, discusses how the company integrates quality

throughout the product life cycle. Morris, who has

been with the company for 12 years, leads three groups

at SAS: Tools and Infrastructure, Testing Integration,

and Process and Research.

QD: How does quality come into play

in the process of developing your software?

Morris: It starts with our employees;

they're qualified and loyal. We have a very low turnover

rate because of our environment; satisfied employees

create satisfied customers.

Infrastructures are in place to support quality--like

R&D trainers to educate new hires in our internal

processes and technologies. We organize so that the

testers and developers are sitting side by side, working

together to create a quality product. Also, we try

to get the technical support team and the marketing

strategists located nearby or at least promote interaction

to ensure that the right products are delivered. We

have internal tools to help the developers and testers

work seamlessly along with automated internal reports

to track the release progress. We use quality management

systems to document our processes and create a model,

which helps us develop and sustain repeatable processes.

QD: How has the software quality

process changed in the decade that you've been with

SAS?

Morris: The awareness that quality

is the responsibility of everyone working on the software

project now permeates the organization. We're using

complete data to inform the team and management about

the quality status. It's on our internal Web so every

employee has access to it. And we're open to new models,

such as prototyping and peer programming. During the

past several years, we've been using more tools to

help us automate reports and tests.

QD: How involved is top management

in the quality process?

Morris: Top management sees it as

a priority. Jim Goodnight, our CEO, is a programmer

himself. He understands the need to have a quality

system. Like Goodnight, our CTO Keith Collins understands

the value of a quality system. He wants to be proud--we

want to be proud--of what we deliver.

Just this week [Goodnight] hosted an internal Webcast,

and he was talking about how he really enjoys programming

and wishes he had more time to do it. He's a man who

understands what programmers have to go through, and

he's also focused on quality. So, quality does come

from the top down as well as the bottom up.

Because we lease our software on a yearly basis,

we have to continuously prove quality to our customers.

That focuses the minds of the developers and sales

force to make sure we're always meeting customer needs

and delivering quality goods because the customer

can decide, "No, thank you. We want to go somewhere

else."

QD: How are defects handled at SAS?

Morris: When customers report a

defect, we mark it as such: a customer-reported problem.

We have reports that highlight the customer-reported

problems to ensure that we address them. The SAS User

Group International conference provides a forum where

developers can talk to customers directly. Ballots

are sent to the customers so we can find out what

they'd like us to improve upon--what their top issues

and feature requests are. We address something from

that ballot every year.

We evaluate our key quality milestones for every

release and determine whether we've met our objectives.

If we haven't, we make hard decisions about cutting

certain features, delaying the schedule, or a combination

of both to ensure a quality product.

QD: What quality improvement suggestions

would you give to software companies that aren't implementing

a quality initiative?

Morris: Metrics are critical to

increase understanding of how their software compares

with what the customer wants and needs and to really

find out where their quality stands. They should hire

people that have quality experience to implement quality

processes. It's a big task. There are lots of measurements,

lots of good practices available, but it does take

time to incorporate them into the fabric of any software

organization.

Communication is key. You have to have good communication

with your customers as well as good communication

within R&D, marketing and throughout the company.

QD: What is your opinion of the

state of quality in software?

Morris: The pressure of having superior

quality while getting to the marketplace in a timely

manner continues to increase. Software product complexity

and operating system interdependence continue to grow.

At the same time, these trends provide us with more

data and better processes and tools to help us with

those challenges. Software quality is growing in maturity,

and it will continue to get better and better. Customers

demand it.

|

IEEE Software Magazine reports that the best commercial

software companies remove about 95 percent of all known

defects before releasing a product to the customer. However,

the industry average is less than 85 percent.

Watts Humphrey of Carnegie Mellon University's Software

Engineering Institute estimates that for every 1,000 lines

of code that software professionals create, there are about

100 defects.

The Standish Group's Software Chaos report states that

the software performance success rate is about 30 percent,

and runaway and failed projects are common.

If these statistics regarding the quality of software

don't make you cringe, you must have never used a computer.

Surely everyone who has can relate a story about how software

bugs have affected his or her work. Your computer locked

up before you had a chance to save that important report;

your Web page was down and you couldn't figure out why;

you called tech support to report a problem only to have

them tell you, "We're already aware of that defect,

and you owe us $35 for the phone call." But can the

state of quality in software really be as bad as the statistics

suggest? And if so, what can software development companies

do about it? This article will attempt to answer these questions.

What is the state of software quality today? It really

depends on whom you ask. Various reports surface every year

or so that attempt to explain where the United States stands

in terms of software quality, but there seem to be as many

opinions as there are experts on the subject.

"There's been some improvement in software quality

over the years," explains Herb Krasner, founder of

the Software Quality Institute at the University of Texas.

"About five years ago, The Standish Group was reporting

that the software project performance success rate was about

25 percent, meaning that 75 percent of all software projects

that were undertaken were ultimately unsuccessful. Today,

it's up to 30 percent; so yes, there is slight improvement."

Carolyn Fairbank, CEO of the Quality Assurance Institute,

believes that software quality will remain below par until

organizations restructure their thinking to be based not

upon deadlines, but upon good processes. "We're far

too focused on product delivery, not process capability,"

she argues. "We're too busy trying to get the product

out the door. Granted, this is a market-driven phenomenon,

but we'll have to change that deadline-driven attitude to

one of good processes. If you get the process right, the

product will have a far better chance at success. Unfortunately,

many IT professionals still don't quite understand the concept

of process management."

"In the beginning of a new technology's life cycle,

there's a time when it's really exciting but crappy in terms

of quality," explains Mark Minasi, technology writer

and author of several books on software, including The Software

Conspiracy: Why Software Companies Put Out Faulty Products,

How They Can Hurt You, and What You Can Do About It (McGraw-Hill

Trade, 1999). "We've been in the software business

around 55 years, and by now we should be in the part of

the life cycle where quality becomes important. I like to

ask people, 'How would you feel if Interstate 95 was completely

computerized and a Pentium 4 was running it?' They all say,

'I'd never get on that.' We don't trust software, and it's

a terrible shame."

Experts cite several reasons software companies excuse

themselves from investing more heavily in quality practices:

"Our customers aren't complaining; therefore they're

satisfied." That's wrong, says Fairbank. On the contrary,

customers feel that they have no other choice but to put

up with defective software, so they don't bother complaining.

In other words, the public has become used to poor-quality

software. However, Fairbank warns companies against this

"like it or leave it" mentality. "In the

beginning, if you wanted a desktop you either went with

Apple or Microsoft," she explains. "But, during

the last several years, new operating systems like Linux

have emerged, which is giving some of the larger companies

a run for their money. Customers are slowly starting to

realize that they really do have alternatives and, more

important, they have legal recourse."

"Our customers aren't complaining; therefore they're

satisfied." That's wrong, says Fairbank. On the contrary,

customers feel that they have no other choice but to put

up with defective software, so they don't bother complaining.

In other words, the public has become used to poor-quality

software. However, Fairbank warns companies against this

"like it or leave it" mentality. "In the

beginning, if you wanted a desktop you either went with

Apple or Microsoft," she explains. "But, during

the last several years, new operating systems like Linux

have emerged, which is giving some of the larger companies

a run for their money. Customers are slowly starting to

realize that they really do have alternatives and, more

important, they have legal recourse."

"We've tried quality and we didn't see any results."

Like all quality initiatives, results aren't always immediately

noticeable--it's what Fairbank refers to as the software

industry's tendency to be instant gratification-oriented.

"We've tried quality and we didn't see any results."

Like all quality initiatives, results aren't always immediately

noticeable--it's what Fairbank refers to as the software

industry's tendency to be instant gratification-oriented.

"The improvement I see with companies that invest

in software quality is 10 times, easily," adds Krasner.

"There's a lag time between the investment and the

payoff, and it varies by organizational size. So, once you

get them to invest in improving the quality, management

has to be patient enough to wait to see the return on the

bottom line."

"Our customers want new features, not better quality."

This is another misconception, say the experts. "Marketing

is constantly saying, 'It's got to have new features; otherwise

we can't compete,' " says Minasi. "We need to

convince software vendors that it's perfectly OK to spend

less time on features and more time on quality. Who really

needs Mongolian character sets? If you want to sell me your

newest version, make it crash-proof."

"Our customers want new features, not better quality."

This is another misconception, say the experts. "Marketing

is constantly saying, 'It's got to have new features; otherwise

we can't compete,' " says Minasi. "We need to

convince software vendors that it's perfectly OK to spend

less time on features and more time on quality. Who really

needs Mongolian character sets? If you want to sell me your

newest version, make it crash-proof."

"In order to get the product out in a timely manner,

we must sacrifice some quality." Software development

is a time-to-market industry, which may cause some vendors

to assume this attitude. "Software vendors would like

to provide a quality product, but they've got to get it

out to market before someone down the street does,"

explains Fairbank. "We've accelerated our time-to-market

by leaps and bounds, but that doesn't mean quality has improved.

In fact, the companies that don't have quality processes

in place are the ones that have trouble getting a product

out to market in the speed at which it needs to be delivered."

"In order to get the product out in a timely manner,

we must sacrifice some quality." Software development

is a time-to-market industry, which may cause some vendors

to assume this attitude. "Software vendors would like

to provide a quality product, but they've got to get it

out to market before someone down the street does,"

explains Fairbank. "We've accelerated our time-to-market

by leaps and bounds, but that doesn't mean quality has improved.

In fact, the companies that don't have quality processes

in place are the ones that have trouble getting a product

out to market in the speed at which it needs to be delivered."

Minasi describes it as the "iron triangle":

You can have it fast; you can have it cheap; you can have

it good. Sounds nice, but the customer is only allowed to

pick two. "Software vendors think that customers will

choose fast and cheap," he says.

"Top management doesn't care about quality." Yes,

they do. However, those who pitch quality to top management

must explain it in terms they understand: What is the cost

of poor-quality software?

"Top management doesn't care about quality." Yes,

they do. However, those who pitch quality to top management

must explain it in terms they understand: What is the cost

of poor-quality software?

"It's impossible to create low-defect software; by

nature, software contains bugs." The experts disagree.

Software development companies that don't use quality processes

have high chances of creating bug-ridden software simply

because they're starting from scratch every time they develop

something new, explains Minasi. As an example, he compares

software companies' processes to The Boeing Co.'s. A significant

portion of new product development at Boeing lies within

the development and testing phases. Not one part is built

before it's been tested in theory and on paper. This way,

Boeing can be almost 100-percent sure that the product will

work even before they've built it.

"It's impossible to create low-defect software; by

nature, software contains bugs." The experts disagree.

Software development companies that don't use quality processes

have high chances of creating bug-ridden software simply

because they're starting from scratch every time they develop

something new, explains Minasi. As an example, he compares

software companies' processes to The Boeing Co.'s. A significant

portion of new product development at Boeing lies within

the development and testing phases. Not one part is built

before it's been tested in theory and on paper. This way,

Boeing can be almost 100-percent sure that the product will

work even before they've built it.

In contrast, many software makers create a new program

and then test it for defects, leaving them prone to mistakes.

Another problem experts cite is that software companies

are often immune to the consequences of their poor-quality

product. "With some exceptions, software companies

have been shielded from litigation for years," explains

Fairbank. "The customer will one day say, 'We're fed

up with this, so we're not buying your product anymore.'

When companies take the fall from either litigation or financial

disaster, we'll start to see an accelerated trend toward

software quality."

The tricky part, however, is convincing software companies

that it's in their best interest to invest in quality now.

This involves showing top management the bottom-line results

and making a culture change toward quality throughout the

entire organization. It also means teaching software development

companies about the various methods of attaining that goal.

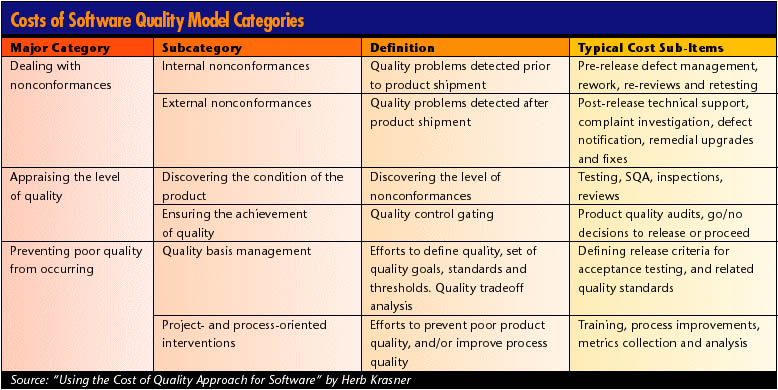

There are several approaches a software developer can

take when implementing quality practices. Krasner has developed

an approach called the "cost of software quality,"

which outlines the economic benefits of delivering good

quality software. The cost of quality approach has long

been used in the manufacturing industry, and Krasner has

expanded on that idea to include software development.

CoSQ defines key dimensions of software quality, including

the level of customer satisfaction; the degree to which

software has value for its stakeholders; key attributes

such as reliability, usability and maintainability; the

degree to which a software product is defective and the

implementation of quality processes. (See page 34.)

In his report, "Using the Cost of Quality Approach

for Software," Krasner explains that companies need

to answer three questions: How much does poor software quality

cost? How much does good software quality cost? How good

is our software quality? Once these questions are answered,

the software providers can compare quality costs to overall

software production costs and software profits, compare

quality costs to benchmarks and norms, better analyze product

quality to improve their competitive situation, measure

improvement actions and bottom-line effect of quality programs,

visibly see previously hidden costs related to poor quality,

and more clearly see the economic tradeoffs involved with

software quality.

"By putting the cost of quality model into action

in an organization, what immediately becomes obvious to

management and the executives is the amount of money they're

losing on fixing bugs and delivering poor-quality products,"

comments Krasner. "They were never able to quantify

that before, so they could only guess about how it was affecting

their bottom line. The cost of quality model gives them

results in a form that they understand: dollars."

Another approach to software quality improvement is the

Capability Maturity Model. The Carnegie Mellon Software

Engineering Institute, which developed the CMM, describes

it as the outline of the principles of software process

maturity that assists software organizations in improving

their software processes in terms of product evolution.

It comprises five maturity levels (This information can

be found at the SEI Web site: www.sei.cmu.edu):

Initial. The software is characterized as specialized

(ad hoc) and, occasionally, even chaotic. Few processes

are defined and success depends on individual effort.

Initial. The software is characterized as specialized

(ad hoc) and, occasionally, even chaotic. Few processes

are defined and success depends on individual effort.

Repeatable. Basic project management processes

are established to track cost, schedule and functionality.

The necessary process discipline is in place to repeat earlier

successes on projects with similar applications.

Repeatable. Basic project management processes

are established to track cost, schedule and functionality.

The necessary process discipline is in place to repeat earlier

successes on projects with similar applications.

Defined. The software process for both management

and engineering activities is documented, standardized and

integrated into a standard software process for the organization.

All projects use an approved, tailored version of the organization's

standard software process for developing and maintaining

software.

Defined. The software process for both management

and engineering activities is documented, standardized and

integrated into a standard software process for the organization.

All projects use an approved, tailored version of the organization's

standard software process for developing and maintaining

software.

Managed. Detailed measures of the software process

and product quality are collected. Both the software process

and products are quantitatively understood and controlled.

Managed. Detailed measures of the software process

and product quality are collected. Both the software process

and products are quantitatively understood and controlled.

Optimizing. Continuous process improvement is enabled

by quantitative feedback from the process and from piloting

innovative ideas and technologies.

Optimizing. Continuous process improvement is enabled

by quantitative feedback from the process and from piloting

innovative ideas and technologies.

The CMM contends that as an organization moves up these

five levels, the results are predictability, effectiveness

and control of the organization's software.

Other ways to systematically improve software quality

are through established standards. The Institute of Electrical

and Electronics Engineers produces more than 30 percent

of the world's published literature in electrical engineering,

computers and control technology. This includes more than

40 standards related to engineering terminology, process

documentation, quality tools, project management, safety,

dependability and other software quality issues. To learn

more about specific IEEE standards, visit http:/href="http://qualitydigest.com/standards/index.lasso".ieee.org/software.

The International Organization for Standardization also

develops specific standards related to information technology

and software engineering, including software testing requirements,

software product evaluation, software process assessment

and others. A complete list of software-related ISO standards

is available at www.iso.org.

Although they differ about the state of quality in software

today, experts agree that it will continue to improve. Minasi

believes that as software developers realize that there

are only so many special features they can add, the focus

will move toward quality. "Once quality becomes a perceived

possibility, once it becomes something you can buy, people

will upgrade to that system," he suggests.

Fairbank says that software companies can improve quality

by adopting an enterprisewide quality culture. "There

are small things an organization can do to make an immediate

bottom-line improvement," she states. "But, instilling

the philosophies of quality into an organization takes a

culture change that doesn't happen overnight. The ones that

stay in it for the long haul have seen tremendous results

via improved customer satisfaction, outstanding products

and services, heightened employee morale, and substantial

ROI."

Krasner sees a slow but steady trend toward quality. "In

10 years, instead of a 30-percent success rate on our software

projects, I hope we'll have a 75-percent success rate,"

he says. "My hope is that instead of losing about $60

billion a year because of software quality problems, we'll

only be losing $30 billion."

He also agrees with Fairbank that a culture change is

needed. "The catalyst for change is re-educating people

who are in decision-making positions to understand that

quality methods are good for business. We've educated the

developers and the project managers, and they understand

why quality is important. Now it's time to prove it to the

people above them."

Kennedy Smith is Quality Digest's associate editor. Letters

to the editor regarding this article can be sent to letters@qualitydigest.com.

|